Saabira Chaudhuri recently released her book, 'Consumed: How Big Brands Got Us Hooked on Plastic’. For a decade, Saabira has written about the consumer goods industry for The Wall Street Journal from London. She has reported on large, publicly traded companies as well as broader industry trends in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere, with a particular interest in how our consumption of everyday products is increasingly affecting our environment and our health. To understand the inspiration for her book, we reached out to Saabira with some burning questions, and here are her answers:

Q. In Consumed - How Big Brands Got Us Hooked on Plastic, you retrace the story of sachets in India. Can you tell us how, where and by whom were sachets created?

In Consumed, I write about a Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu-based schoolteacher named Chinni Krishnan who, in the late 1960s, started a business repackaging powdered pharmaceutical products into small portions. These were aimed at poorer people who couldn’t afford larger packs. At the time in India, a handful of dry products like tea and gutkha were sold in small sachets, but Chinni Krishnan wanted to go further. He began looking for ways to package liquids in sachets, eventually creating a pouch made from polyvinyl chloride. He used the pouch to sell a new shampoo brand he called Velvette. After he died, his son, CK Ranganathan, launched another shampoo brand called Chik, also in sachets. He employed a particularly creative marketing model, going from village to village in South India to conduct hair-washing demonstrations. Packaged in sachets, Chik shampoo was affordable to millions of Indians who had otherwise used reetha (soap berries) and amla (gooseberries) or just bar soap. Sales began to tick up.

It wasn’t long before Hindustan Lever – Unilever’s India subsidiary – took notice. Starting in 1987, Hindustan Lever began putting its Sunsilk and Clinic shampoo in sachets. It coupled this with mass-market advertising, explaining how sachets should be used and how using commercial shampoo could lead to straight, shiny hair. A few years later, when Procter & Gamble entered India’s shampoo market, the Cincinnati-based consumer goods giant launched Pantene in bottles but also in sachets, which by then accounted for the vast majority of shampoo sales in India. The multinationals didn’t limit their ambitions to the south. They took sachets across the country, including to some of its most remote areas, places that didn’t have organized waste collection, let alone recycling.

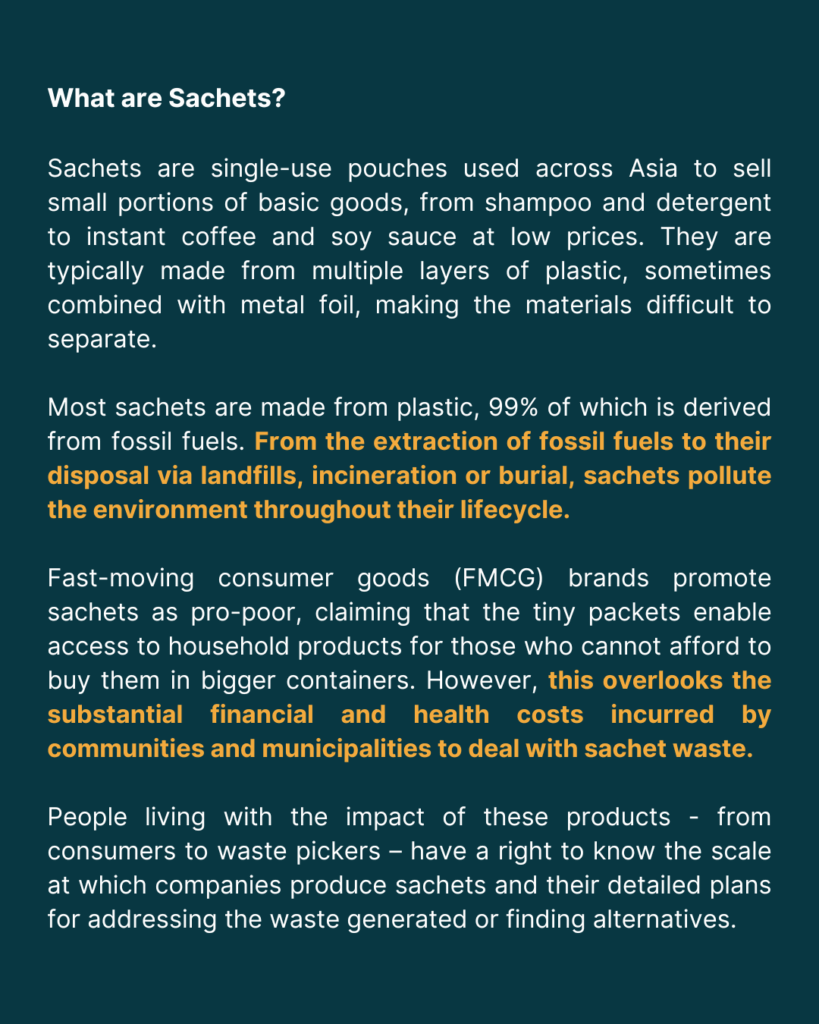

Q. What exactly is the issue with sachets? Why has their proliferation created so many problems for both corporations and communities?

Every sachet discarded today is landfilled, burned, dumped or littered – many near or in water bodies where they fragment into microplastics. The sachets were never designed to be recycled – they’re made of a blend of plastic and aluminium that is expensive to separate. Their size also makes them expensive to collect and sort. A main problem is just how many of them there are - in 2021, in India alone, nearly 41 billion shampoo packages were sold, of which 99% were sachets. Sachets have spiralled well beyond shampoo and are used for everything from hair oil and pickle to laundry detergent and mosquito repellent.

Activists continually pressure Unilever and others to stop selling sachets and the tiny plastic pouches have turned into a reputational bugbear. The companies argue that scrapping sachets would mean poor people couldn’t access their brands. The flip side, of course, is that the environmental harms from dumping and burning used plastic are felt most by poorer people.

Through my reporting for Consumed, I learned that the popularity of sachets came as a surprise even to the companies that created them. Companies like CavinKare, Unilever and P&G saw sachets as a tool to sell to India’s poorest but in fact, sachets have been adopted by a far wider swathe of the population. They’re convenient, portable and allow a wide variety of choices. Strangely, in India, they are often more economical than buying bottles of shampoo or detergent, flying in the face of industry precedent that says bigger is cheaper.

Companies are definitely cognisant of the problems sachets are causing but say they haven’t found an alternative material that can as effectively protect the product within.. While reuse models have been explored, they’ve never scaled because buying sachets is cheap, convenient and people have access to a wide variety of brands.

Q. Can you elaborate on some of the tactics used by big brands in the Global North and the Global South to get us hooked to plastic?

A big message globally over the past eighty years has been that plastics are synonymous with hygiene. Starting in the 1930s, companies like DuPont began pushing the idea that wrapping food in plastic kept germs away and that unwrapped food was not just dirty but irresponsible - a hazard to a family’s health.

Another big hook is convenience, a value that really took root in the 1950s. The industry developed disposable everything over this decade and the message to overworked American housewives who were increasingly entering the workforce was that plastics could free them from drudgery.

Of course, while plastics can help protect food and make life more convenient, they’ve also helped companies slash costs, lengthen supply chains and spur consumption – all of which have combined to bring about a massive overuse of single-use plastic.

A tactic companies have employed to keep people hooked on plastic – and disposability – is warning of huge price rises should lawmakers move to change anything about the way business is currently done, where the cost of dealing with waste is outsourced onto taxpayers and the end-of-life costs of plastic are in no way reflected in the price consumers pay.

Companies have also regularly funded studies called “life cycle analyses” espousing their position (which is usually that plastics are environmentally the best material for any particular use case), often without disclosing that they’re the ones behind the studies. Life cycle analyses are very complex, relying on a whole range of assumptions and the results can vary hugely depending on who is conducting the studies and what assumptions are made.

Q. If there’s one idea or key takeaway from the book on the issue of plastic pollution, what would it be?

If I had to pick just one, it’s that none of the many high-profile promises companies have noisily made over the past four decades to slash plastic use and waste have worked. Far from tackling the problem, companies are using more plastic than ever and are falling even further behind.

I have an analogy in my book where I compare the big consumer goods companies to drug addicts – they’re aware they have a problem, many of them genuinely see the need to cut back on single-use plastic, but they’re so deeply dependent on disposability as a business model that they’re unable to make changes. And so they employ the same tactics year after year, make the same overblown promises, fund the same sorts of studies justifying their existing business models, and roll out the same “pilots” and “trials” that never scale.

I see regulation as akin to rehab - we as consumers need to push our elected representatives to rewrite the rules by which companies are allowed to do business. We also need to push companies themselves to stop lobbying against proposed regulations that would cut waste and emissions. We should not just vote with our wallets but also call out companies that greenwash or act irresponsibly, telling them of our displeasure and how we’ll be shopping elsewhere from hereon.

Remaining silent and leaving it up to companies to voluntarily make the necessary changes will never lead to the big shifts we need to truly slow the production of plastic, reduce our dependence on disposable products and packaging and cut waste. The various stories in Consumed – which span several decades and show the same patterns across all of these – underscore this.

Q. In your final chapters, you speak of where we are today, and where we go from here. Do you feel the Global Plastics Treaty offers some hope, or a framework for other policies on curbing the issue of plastic pollution?

Having a global treaty in place could be useful, given nothing but regulation will push companies to change how they do business. How useful it is depends on what can be agreed on, how strictly it’s implemented and who signs.

When it comes to policy measures, the lowest-hanging fruit involves pushing companies to think about whether they need to use disposable packaging at all and, if they do, how to design it so that it’s easy to recycle or reuse, is free of harmful chemicals and doesn’t shed microplastics. Extended producer responsibility, a policy that transfers the cost of dealing with the waste generated by products from taxpayers to the companies that make the products, is a first step towards funding waste collection infrastructure. A more sophisticated version of EPR involves “eco-modulated” fees, which are levied based on how environmentally harmful a product or packaging is. This should ultimately push companies to make better design choices.

Reuse and waste reduction targets could spur the development of standardized packaging for reuse and refill – along with collection and washing facilities to service these. Overall, laws that narrow the types of plastics (and chemicals) allowed on the market, and the uses these are allowed for, could help us begin to get a handle on waste but also improve human health, which is increasingly a concern because of the thousands of chemicals that are used in plastics. It’s important to say that simply switching to another disposable material, like paper, comes with its own environmental consequences, and generally, this isn’t a path I advocate for. To truly break free from the cycle of make-consume-throw we need to think about shifting overall behaviour and the economics underpinning how we consume.

Ultimately, while a global treaty could play an important role in mandating these kinds of laws across countries, real progress will also depend on public engagement. Individuals need to become more informed and actively involved—holding companies accountable for their role in driving plastic dependency, and reflecting critically on our own habits as consumers within an economy built on endless consumption. Systemic change won’t happen without pressure from the ground up, alongside top-down regulation.

Want to know more?

(Photo Essay) The Story of Sachets

(Report) Branded: The Sachet Scourge in Asia

(Report) Sachet Economy: Big Problems in Small Packets

(Report) Missing the Mark: Unveiling Corporate False Solutions to the Plastic Pollution Crisis