Plastic pollution is one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time. Tackling it requires more than just cleanup efforts or lifestyle changes, it demands scientific research that can guide the implementation of regulations and effective solutions. From understanding where plastic ends up to revealing how it harms ecosystems and human health, scientific research plays a critical role in addressing the crisis and supporting the adoption/implementation of the most effective measures.

But here’s the catch: translating that science into something the public can understand and act on isn’t easy. The language of research is often dense and technical. Terms like “biodegradable,” “microplastics,” or “chemical recycling” are frequently misunderstood, misused or co-opted for greenwashing. And because the effects of plastic pollution can be long-term and invisible, like chemical leaching or microplastics in our food, it’s even harder to make the impacts feel urgent and personal.

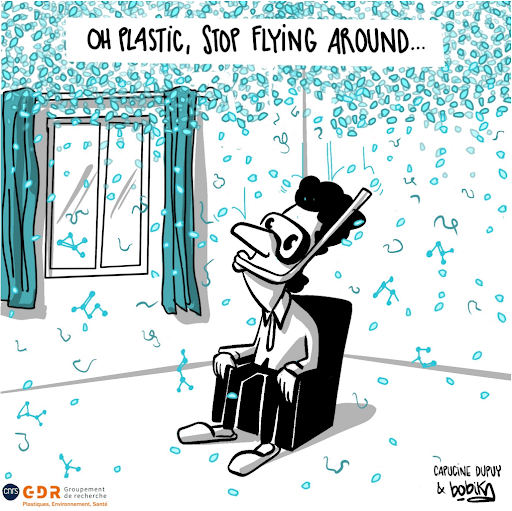

To bridge this gap, a group of scientific researchers in France, the Groupement de Recherche on Plastics, Environment, and Health (GDR), collaborated with scriptwriter Capucine Dupuy and illustrator Bobika to create a series of cartoons that communicate scientific findings in a clear, humorous, and visually engaging way. We sat down with Professor Mathieu George of the University of Montpellier and Capucine Dupuy to talk about this creative collaboration: how it started, why humour helps, and what they’ve learned about making scientific communication appealing to public audiences whilst maintaining scientific rigour.

BFFP: Hi Mathieu and Capucine, thank you so much for speaking with us today. Before we dive into these new cartoons, could you both introduce yourselves and share a bit about your background, and what brought you to this project on using cartoons to communicate plastic pollution research?

Mathieu: My name is Mathieu George. I’m a professor at the University of Montpellier. My research background is in materials science, more specifically, I began by studying cracks in glass, which had nothing to do with plastics at the time.

But over time, I became interested in how plastics crack and degrade. Around ten years ago, some colleagues, especially biologists, approached us with questions. They were seeing plastics everywhere in the ocean but didn’t understand the material itself. That’s when I really got involved in plastic pollution research: studying how plastics fragment, crack, and degrade in the environment, to help us better understand their long-term impact.

At the same time, together with my colleague Pascal Faure here in Montpellier, we started developing the idea of a research network that could bring together scientists from different disciplines concerned with plastic pollution: chemists, physicists, biologists, oceanographers. That network became the Groupement de Recherche (GDR) on Plastics, Environment and Health. I can tell you more about it a bit later.

Capucine: And I’m Capucine Dupuy. I’m a scriptwriter who works mainly on environmental comics and books. What I do is read dense, technical reports, things most people never read because they’re too technical, too dry, and, honestly, kind of unappealing, and I turn them into stories using words and images.

I started working on plastics about five years ago, kind of by chance. It began with a short series of 12 cartoons and it never really stopped. From 12, it became 15, then 18, then 21… and now I’ve done over 28. That led to a first comic book, then a second, then a third, and eventually public talks as well. Right now, I’m working on a book with a special focus on toxicity in plastics.

BFFP: Going back to you, Mathieu: could you explain a bit more about the GDR and the role it plays within the scientific community in France, and beyond?

Mathieu: So, the Groupement de Recherche, or GDR, is a network of researchers officially supported by the CNRS, which is France’s national scientific research center. There are many GDRs, usually organized around very specific scientific fields. But what makes ours a bit different is that it’s highly multidisciplinary.

In our case, we bring together researchers from a wide range of backgrounds: chemistry, biology, physics, oceanography, toxicology, all working on different aspects of plastic pollution. That diversity is one of our strengths, and it reflects a growing recognition within CNRS that science needs to be more engaged with society’s big challenges. The idea is to make the research more visible and relevant to people beyond the lab.

Our network started in 2019, so it’s been about six years now. Initially, it was focused specifically on polymers and the ocean, that was even the original name. But we’ve since expanded our scope significantly. Today, we include research on human health, soil, the atmosphere, really, all environments affected by plastics. That’s why we renamed it: GDR Plastics, Environment and Health.

It’s been very successful at building connections. We now have around 60 member laboratories and more than 250, possibly over 300, individual researchers involved. It gives us a great platform to collaborate across disciplines, often with people we wouldn’t normally interact with. We meet regularly to exchange ideas, and the discussions can range from microplastic toxicity to ocean currents, to the physics of plastic cracking which is my field.

BFFP: That’s incredible, I didn’t realize the network was that extensive. Thank you for including those numbers. It really helps paint the picture.

Now I’d like to shift gears a little and talk more about this specific project and your collaboration on cartoons. What inspired you to use cartoons as a way to communicate scientific research on plastic pollution?

My thinking behind this question is that, often, scientific research stays within academic circles. It takes effort to bring it into public spaces and make it accessible. So what led you to this creative approach?

Mathieu: Yes, I think one of the great strengths of our network is that we’re working on an issue that affects everyone. Plastic pollution is a widely recognized problem. It’s in the media, it’s in daily conversations. So as researchers, we can’t just stay in our academic bubble anymore. People want to understand what’s going on.

I’ve noticed a change personally. A few years ago, when I talked to friends about my work, they weren’t particularly interested. Now, when I mention I research plastic pollution, people immediately engage. They have opinions, experiences, and lots of questions, and often, they also have a lot of misconceptions.

That’s really motivating. It pushes us to find new ways to communicate clearly with a broad audience and not just other scientists, but also the general public, policymakers, and industry. That’s why working with someone like Capucine, who’s already well-known for turning complex science into compelling narratives through cartoons, was so exciting.

Capucine: Yes, it actually builds very naturally on my previous work. Over the years, I’ve been invited to speak at conferences and panels, where I met several scientists, at first just one or two. And I kept having the same reaction: “Wow, what they’re doing is so important. How come no one knows about it?”

I often felt like a kid wanting to stand on a chair and shout, "Listen to them!" That frustration, that urgency, was really the starting point for me. I wanted to understand their work and then help others understand it too.

One day, Jean-François Ghiglione, one of the members of the GDR, invited me to attend their annual conference. Just as an observer, no pressure. So I went to the south of France and spent two days there. It was fantastic. I was a bit like a tourist at first but that freedom let me absorb a lot. After that, we kept crossing paths at events, and eventually the idea of a collaboration came up.

First, I try to understand. So I dig, I ask a lot of questions, I really push the scientists to explain. Then I synthesize: What’s important? What’s new? What’s counterintuitive? And finally, I translate all of that into words and images. It’s a bit like sculpting. Starting rough, and slowly carving it down to the essential message.

BFFP:

So after going through all those steps, what are the key messages you’re trying to get across through these cartoons? What do you hope people understand when they read them?

Capucine: The first thing is the complexity of plastics. I’ll give you an example. At that first GDR meeting I attended, it was Monday morning, everything was going really fast: super technical, full of abbreviations. I felt my whole body tensing up with stress. I thought, “I’ll never understand this. It’s too much.”

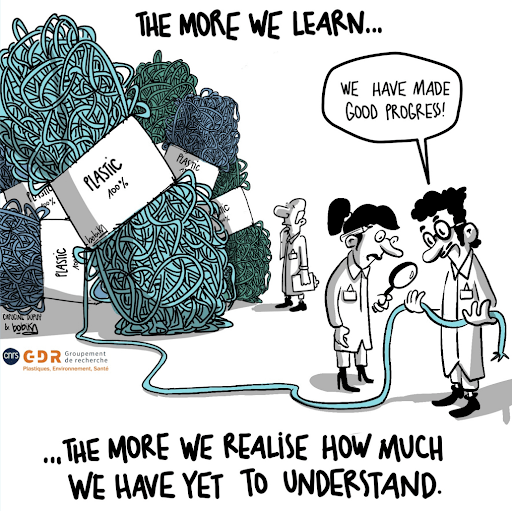

At lunch, someone I didn’t know came up to me and asked if I was okay. I told them honestly, I felt totally lost, like I wasn’t sure I’d be able to explain anything I’d heard. And they just smiled and said, “Don’t worry. No one here really understands plastics.”

I was shocked. These were top scientists, people who had spent years, even decades, on this issue. But it really drove home how complex plastics are, even for the experts. So that’s the first message I want to share: this is not a simple problem.

The second thing is about honoring academic work. I’m genuinely moved by how many people dedicate years of their lives to studying plastics. That alone should tell us something. Plastic is not just a neutral, convenient material. It’s complicated, and its impacts are serious.

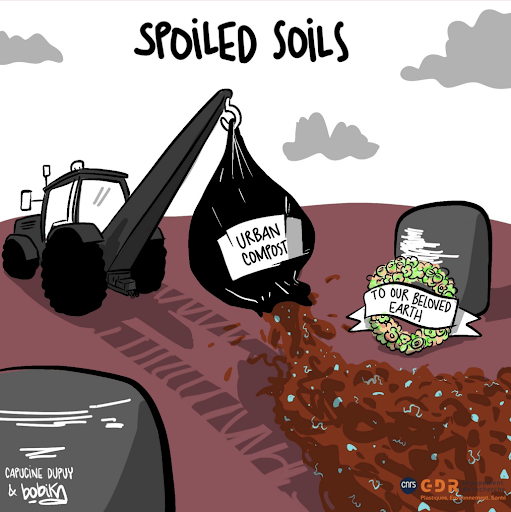

And third, I try to highlight specific insights that people may not know. Like the fact that urban compost can carry microplastics into agricultural fields. Or that our homes and cars are full of micro- and nanoplastics, often in ways we don’t realize. I want people to walk away with a better grasp of what plastic pollution really means and why it matters.

Mathieu: I think what Capucine said is really spot on. What I’d add is that the collaboration also gave us something very valuable: an external perspective on our own work.

That was incredibly interesting, even for us as scientists. People often assume we all speak the same language just because we’re in science, but that’s not really true. We come from different disciplines, and sometimes we struggle to fully understand each other, even within the network.

And, of course, what we don’t know about plastics is still far greater than what we do. So having someone like Capucine come in was a powerful way for us to reflect on what we’re doing.

What I really appreciate about the final selection of cartoons is that they highlight aspects of plastic pollution that aren’t always obvious such as insights that offer new perspectives, or that reveal just how complex the issue is. That, to me, is a big success of this project.

BFFP:

I know you already touched a little on the challenges, like how overwhelming it can be to absorb everything. But were there any other challenges you both faced during the collaboration?

Capucine: The main challenge, both in this project and in my work more generally, is always the same: being compact and true at the same time. You need to use just a few words, a few images, but still stay faithful to the complexity of the science. And as I mentioned before, the amount of information at the start is enormous. So distilling that into something short and accessible is always a challenge.

It’s a bit like a funnel. To end up with 15 clean, clear lines, you need to start with about 300. Those lines come from interviews, from notes I’ve taken throughout the day, pages and pages of writing. And then, in the evening, I try to pause, step back, and look at what’s important. What’s urgent? What’s counterintuitive? What actually needs to be said?

Another challenge is something I’ve encountered often, not just in plastics, but across scientific disciplines: scientists are rigorous, and many are uncomfortable with anything that feels like activism. So, for example, jokes or exaggerations, which I sometimes use to make a point or catch attention, can feel risky to them. They don’t want to simplify or caricature the issue.

But for me, humour or visual metaphors aren’t about distorting the truth, they’re a way to help people understand it more quickly. It’s about creating a visual shorthand that connects, that sticks. You’re trying to catch someone’s eye, their curiosity, their time. And in today’s world, that’s incredibly hard.

That tension between precision and communication, it’s still something I wrestle with.

Mathieu: Yes, I was thinking about the same challenge as Capucine mentioned. I think it’s really the biggest. And it doesn’t just apply to this cartoon project, it’s the same when we speak to the media, or the public in general.

As scientists, we’re expected to speak only about what has been rigorously proven. So if something isn’t absolutely certain, we don’t want it to be presented as fact. That kind of misrepresentation feels like a failure of integrity, it undermines our credibility.

And I understand how frustrating that can be, especially for people who are trying to communicate these issues more broadly, or who want to move faster, or more boldly. Because of course, being a scientist doesn’t mean we aren’t concerned, or even that we aren’t activists ourselves. Many of us are deeply concerned about pollution and environmental damage and we want change.

BFFP: So we’ve talked a lot about how communication happened within the cartoon project. But if we zoom out for a moment and think more broadly about how science and communication intersect in the public space, I’d love to ask about how the way people consume information today has shaped that relationship.

Arguably, we live in a world of social media, quick headlines, short attention spans. How has that impacted the way scientists can communicate about their research? And perhaps also, more specifically, when it comes to plastic pollution?

Mathieu: Scientists aren’t exactly known for being great communicators. We’re not always comfortable with it, and honestly, most of us have had no training at all in public communication. So we’re often unsure how to proceed. Some scientists are naturally better at it than others, but overall, it’s not our strength.

One big challenge, especially today, is the speed of modern communication. The pace is so fast, it’s constant and immediate, and that’s just not compatible with the way science works. Scientific research takes time. It often takes years to gather enough evidence to make a solid claim, to be sure of something.

So you have this mismatch: the speed of public discourse and the slow, careful pace of scientific work. And that’s a real difficulty, especially when it comes to something like plastic pollution, which is incredibly complex. It’s not easy to combine these two worlds.

Capucine: Yes, and maybe to add to that from a different angle: images can actually help bridge that gap. They can be a powerful way to fight disinformation, precisely because they go straight to the brain.

A good image makes a reality instantly tangible. It’s something you feel, not just understand intellectually. And that’s really important today, when people have so little time, and even less mental space.

So using pictures can save time, the time Mathieu was talking about. It can also save brain time, which I think is crucial. That’s how you help people understand, and bring them on board.

The goal isn’t to make people feel guilty, or force them into something. It’s not about shaking their conscience or blackmailing them emotionally. It’s more about saying: “Hey, doesn’t this seem a bit absurd?”

The second thing I would say about tackling disinformation is this: when you do share information, it has to be clearly sourced, and based on independent, conflict-free evidence. That matters. Not everyone will check the sources, but some will, and this transparency itself helps build trust.

Of course, I know that nothing is ever fully objective. But if you can show, say, three different sources that agree more or less on the same data or conclusion, that goes a long way.

When it comes to showing plastic pollution, most people think they understand its impact because they’ve seen the iconic images: the plastic soup, the so-called seventh continent. But the real challenge is to show the other side beyond the tip of the iceberg. That means exposing what happens behind the scenes: the production processes, the invisible uses, and the complex chemical journeys. This is where both images and words are powerful tools as they help make the unseen visible.

BFFP:

I’d like to shift focus for a few minutes to the global plastics treaty. Mathieu, I’d love to hear your thoughts on how do scientific findings shape the direction of the treaty? And what research do you think needs to be considered in the next, and possibly final, treaty negotiations coming up in August?

Mathieu:

This really connects to what Capucine was saying earlier. Thanks to years of research, there’s no longer any denying that plastic pollution is everywhere, and that most of it is invisible. The plastic we can see is problematic, of course, but it’s the microplastics and nanoplastics that are often the most concerning. And now, we also have increasing evidence that these particles are not neutral. They affect marine environments, soils, and probably human health too.

This is why it’s crucial for scientists to be present at treaty negotiations. My colleagues who attended spoke with many delegates from different countries. And the reality is, not everyone is fully aware of how widespread or complex the pollution problem really is, especially when it comes to microplastics and the chemicals used in plastic production. Some plastics may seem inert, but they often contain toxic additives, or they absorb other harmful substances once released into the environment.

So it’s important for scientists to bring the data to the table and to clearly say, "This is happening. This is real." That gives decision-makers the responsibility to act with full knowledge of the facts. The French scientific network was quite active in this space, and we also worked closely with researchers from other countries. Together, we formed a kind of coalition of scientists calling for a strong treaty.

We’re also aligned in saying that recycling alone won’t solve this crisis. Nor will so-called "better plastics." These may have a role in specific contexts, but they don’t address the root problem. We need a serious reduction in plastic production. That’s not a popular message with all governments, but it’s essential.

BFFP:

And just to make that more concrete, what would you say are the key measures that an effective treaty must include?

Mathieu:

If we’re serious about limiting plastic pollution, then two things are essential: First, we need to reduce plastic production. That means setting hard limits, and rethinking which products should be made of plastic at all. What can we simply do without?

Second, and very importantly, we need to regulate the chemicals used in plastics. Right now, manufacturers can use thousands of different substances. Instead, we should flip the logic: only approved substances should be allowed in plastic production. Anything else should require special authorization. That would be a major step forward, both for transparency and for protecting health and the environment.

BFFP: This is a big question, but we wanted to bring it in because Break Free From Plastic consists of organizations, activists, and communities around the world, including Indigenous Peoples. Elevating Indigenous and local knowledge systems is a core priority for us in the treaty process. So we’re curious: How can both scientific and traditional knowledge, like that of Indigenous and local communities, be integrated equally in the negotiations and implementation of the plastics treaty?

Mathieu: When I first read this question, I honestly wasn’t sure how to answer. But after thinking about it more, I do believe there are ways traditional knowledge can play a meaningful role, especially as we rethink how to replace plastics in different applications.

Take food preservation, for example. That’s one of the biggest uses of plastic today. We rely on it to keep food from being contaminated or spoiling. But there are likely traditional methods, used for centuries in some cultures, that achieve similar goals without plastics. These practices could be looked at as models or sources of inspiration. I think we really need to explore that more seriously.

Now, I wasn’t directly involved in the treaty negotiations, so I can’t speak to how much space was given to this kind of knowledge in those discussions. But I do think it would be really valuable to have those conversations, to ask what we can learn from Indigenous practices when it comes to living with fewer plastics and designing alternatives that are more sustainable and just.

BFFP: How do you see scientists and civil society best working together to support the adoption of an effective plastics treaty? Where do you think the bridges can be built?

Mathieu: Honestly, what we’re doing right now, having this conversation, collaborating on the cartoon project is already a good example. It’s about finding ways to communicate what science can say, where its limits are, and how we can make that knowledge accessible and useful.

It’s really important to maintain strong links between scientists and civil society. It may sound strange to separate them, as if scientists weren’t part of society, but in practice, we often work in very different spheres. So, creating spaces where we can meet and collaborate is crucial.

At the same time, we scientists also need to acknowledge that we’re not neutral actors in this story. Chemistry and science helped industrialize plastic production in the first place. Now, more and more researchers are becoming aware of the environmental consequences and are asking, What can we do differently? What solutions can we offer? What do we actually know? Because the truth is, we still don’t fully understand the long-term impacts of plastic pollution on the planet.

BFFP: Finally, to end on a lighter note, were there any cartoons from the project that stood out to you personally? Any favorites or themes that resonated with you?

Mathieu:

Yes, I really liked the first cartoon. It shows a researcher analyzing just a tiny fragment of a massive plastic panel and proudly announcing progress. It’s funny, but also very real, that’s exactly what science often feels like.

I found it meaningful on several levels. It captures this disconnect between the scale of the problem: the exponential growth of plastic production and the slower, detailed process of scientific understanding. We focus on very specific questions, but so much remains unknown. That gap is something we need to acknowledge more.

And there’s another layer: the way the cartoon visualizes plastic: those large, entangled molecules. As a physicist, that depiction resonated with me too. It reflects the complexity of the material, the science, and the issue as a whole. So yes, that one really stuck with me.

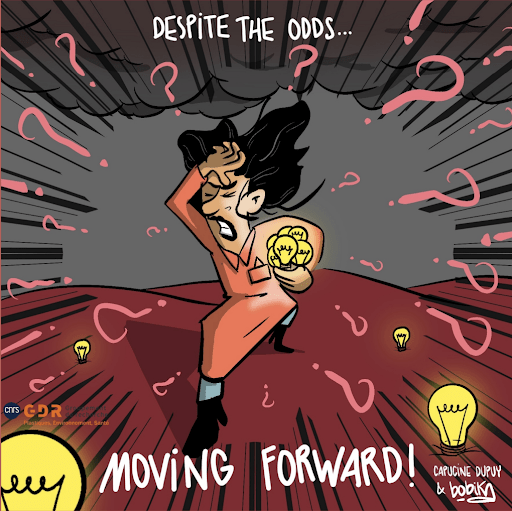

Capucine: It's a little bit difficult to say specifically as this has been a project I have closely worked on with Bobika. But the second one, which depicts the work of scientists caught in this swirling tornado, with dark clouds, but also flashes of light. To me that is what science can feel like - a mix of challenges and breakthroughs. You are deep in the storm, but then something clicks. It is a nice reminder that progress and struggle go hand in hand.

Bringing science out of the lab and into public life isn’t always easy, yet collaborations like this one show it’s not only possible, but essential. By combining rigorous research with creativity and humour, the GDR network and Capucine Dupuy and Bobika are helping more people understand the complex realities of plastic pollution and why it matters. At a time when decisions about creating a plastic pollution free future are being made on the global stage, clear, accessible science is a tool for accountability, action, and change.

Discover the full set of cartoons here and learn more about the work of the GDR.

https://www.gdr-po.cnrs.fr/docs/GDR_2024_en_image_English.pdf